References

Overview of racism and the tobacco industry:

Chamberlain P, Karreman N, Laurence L. Racism and the Tobacco Industry. Bath UK: Tobacco Tactics. https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/racism-and-the-tobacco-industry/

Agaku I, Caixeta R, Carvalho de Souza M, Blanco A, Hennis A. Race and Tobacco Use: A Global Perspective, Nicotine & Tobacco Research 18, (supp 1) 2016, Pages S88–S90, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv225

Exacerbating poverty and undermining education:

Chaloupka FJ and Blecher E. Tobacco & Poverty: Tobacco Use Makes the Poor Poorer; Tobacco Tax Increases Can Change That. A Tobacconomics Policy Brief. Chicago, IL: Tobacconomics, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2018. https://tobacconomics.org/uploads/misc/2018/03/UIC_Tobacco-and-Poverty_Policy-Brief.pdf

Co-opting leaders:

Levin M. The Troubling History of Big Tobacco’s Cozy Ties With Black Leaders. Mother Jones. 2015. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/11/tobacco-industry-lorillard-newport-menthol-black-smokers/

Yerger VB, Malone REAfrican American leadership groups: smoking with the enemyTobacco Control 2002;11:336-345. https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/11/4/336

Targeted marketing:

Heley K, Popova L, Moran MB, et alTargeted tobacco marketing in 2020: the case of #BlackLivesMatterTobacco Control Published Online First: 14 December 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056838.

RJ Reynolds Executive Quote:

Giovanni, J. “Come to Cancer Country, USA, Focus,” The Times of London, August 2, 1992 [quoting Dave Goerlitz, RJ Reynolds’ lead Winston model for seven years, regarding what an R.J. Reynolds executive replied to him when Goerlitz asked why the executive did not smoke].

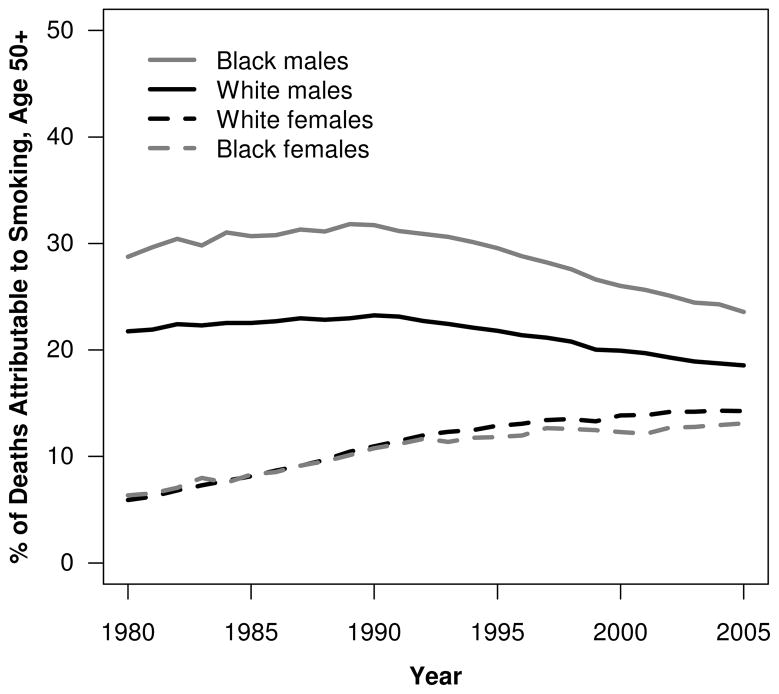

Mortality rates by race in the US

Office US. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General [Internet]. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-cessation-sgr-full-report.pdf.

Menthol in the US:

The African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council. AATCLC Statement on FDA Decision to Ban Menthol. 2021. https://files.constantcontact.com/199ccd27001/bab51938-c4a0-4f9b-a458-a958d06739a1.pdf.

Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (and partners). Stopping Menthol, Saving Lives: Ending Big Tobacco’s Predatory Marketing to Black Communities. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/content/what_we_do/industry_watch/menthol-report/2021_02_tfk-menthol-report.pdf.

Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Menthol Marketing to African Americans. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0208.pdf.

Truth Initiative. Tobacco Use in the African American Community. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/targeted-communities/tobacco-use-african-american-community.

Mullin S, Bassett M. To tobacco companies, Black lives don’t matter. The Hill. https://web.archive.org/web/20210127142921/https:/thehill.com/changing-america/opinion/516531-to-tobacco-companies-black-lives-dont-matter.

Levy DT, Meza R, Yuan Z, et alPublic health impact of a US ban on menthol in cigarettes and cigars: a simulation studyTobacco Control Published Online First: 02 September 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056604.

Hookah:

Alpert Reyes E. L.A. is taking aim at flavored tobacco. Hookah businesses are upset. LA Times 2021. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-06-16/flavored-tobacco-hookah-los-angeles.

Save LA Hookah. https://savelahookah.com/ [organizational website for organization opposing hookah restrictions].

Misappropriating indigenous cultures for tobacco:

D’Silva J, O’Gara E, Villaluz NT. Tobacco industry misappropriation of American Indian culture and traditional tobacco. Tob Control. 2018 Jul;27(e1):e57-e64. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053950. Epub 2018 Feb 19. PMID: 29459389; PMCID: PMC6073916.

Truth Initiative. Why Natural American Spirit cigarettes could be especially dangerous. July 29, 2019. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/traditional-tobacco-products/why-natural-american-spirit-cigarettes-could-be.

New Zealand Tobacco Control Plan

Government of New Zealand (Ministry of Health). Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 Action Plan https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/preventative-health-wellness/tobacco-control/smokefree-aotearoa-2025-action-plan.

Overview of racism and the tobacco industry:

Chamberlain P, Karreman N, Laurence L. Racism and the Tobacco Industry. Bath UK: Tobacco Tactics. https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/racism-and-the-tobacco-industry/

Agaku I, Caixeta R, Carvalho de Souza M, Blanco A, Hennis A. Race and Tobacco Use: A Global Perspective, Nicotine & Tobacco Research 18, (supp 1) 2016, Pages S88–S90, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv225

Exacerbating poverty and undermining education:

Chaloupka FJ and Blecher E. Tobacco & Poverty: Tobacco Use Makes the Poor Poorer; Tobacco Tax Increases Can Change That. A Tobacconomics Policy Brief. Chicago, IL: Tobacconomics, Health Policy Center, Institute for Health Research and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, 2018. https://tobacconomics.org/uploads/misc/2018/03/UIC_Tobacco-and-Poverty_Policy-Brief.pdf

Co-opting leaders:

Levin M. The Troubling History of Big Tobacco’s Cozy Ties With Black Leaders. Mother Jones. 2015. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/11/tobacco-industry-lorillard-newport-menthol-black-smokers/

Yerger VB, Malone REAfrican American leadership groups: smoking with the enemyTobacco Control 2002;11:336-345. https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/11/4/336

Targeted marketing:

Heley K, Popova L, Moran MB, et alTargeted tobacco marketing in 2020: the case of #BlackLivesMatterTobacco Control Published Online First: 14 December 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056838.

RJ Reynolds Executive Quote:

Giovanni, J. “Come to Cancer Country, USA, Focus,” The Times of London, August 2, 1992 [quoting Dave Goerlitz, RJ Reynolds’ lead Winston model for seven years, regarding what an R.J. Reynolds executive replied to him when Goerlitz asked why the executive did not smoke].

Mortality rates by race in the US

Office US. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General [Internet]. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2020-cessation-sgr-full-report.pdf.

Menthol in the US:

The African American Tobacco Control Leadership Council. AATCLC Statement on FDA Decision to Ban Menthol. 2021. https://files.constantcontact.com/199ccd27001/bab51938-c4a0-4f9b-a458-a958d06739a1.pdf.

Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids (and partners). Stopping Menthol, Saving Lives: Ending Big Tobacco’s Predatory Marketing to Black Communities. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/content/what_we_do/industry_watch/menthol-report/2021_02_tfk-menthol-report.pdf.

Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. Menthol Marketing to African Americans. https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/factsheets/0208.pdf.

Truth Initiative. Tobacco Use in the African American Community. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/targeted-communities/tobacco-use-african-american-community.

Mullin S, Bassett M. To tobacco companies, Black lives don’t matter. The Hill. https://web.archive.org/web/20210127142921/https:/thehill.com/changing-america/opinion/516531-to-tobacco-companies-black-lives-dont-matter.

Levy DT, Meza R, Yuan Z, et alPublic health impact of a US ban on menthol in cigarettes and cigars: a simulation studyTobacco Control Published Online First: 02 September 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056604.

Hookah:

Alpert Reyes E. L.A. is taking aim at flavored tobacco. Hookah businesses are upset. LA Times 2021. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-06-16/flavored-tobacco-hookah-los-angeles.

Save LA Hookah. https://savelahookah.com/ [organizational website for organization opposing hookah restrictions].

Misappropriating indigenous cultures for tobacco:

D’Silva J, O’Gara E, Villaluz NT. Tobacco industry misappropriation of American Indian culture and traditional tobacco. Tob Control. 2018 Jul;27(e1):e57-e64. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053950. Epub 2018 Feb 19. PMID: 29459389; PMCID: PMC6073916.

Truth Initiative. Why Natural American Spirit cigarettes could be especially dangerous. July 29, 2019. https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/traditional-tobacco-products/why-natural-american-spirit-cigarettes-could-be.

New Zealand Tobacco Control Plan

Government of New Zealand (Ministry of Health). Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 Action Plan https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/preventative-health-wellness/tobacco-control/smokefree-aotearoa-2025-action-plan.